A current Medline search on the keywords "operating, room, future" yields 19 articles mentioning powerful new technology but few practical details on how to plan a new OR. Generally managers involved in this process visit recently built ORs, sometimes overseas, to gather ideas. When asked, "what would you do differently next time?" all say they would have included more storage and not allow this to be cancelled to save money.

Major problems include clutter by cables and tubing on the floor within the OR, and failure to plan for the flow of patients who are having surgery on the day of admission and do not need to go to the ward first. Other problems include noise associated with highly reflective surfaces and unsuitable temperature levels controlled by remote technicians rather than within the OR.

There are repeated failures to learn from past mistakes. One method of reducing them is Post-Occupancy Evaluation (Preiser 1988) a neglected technique in architecture. Errors can be reduced further by "Pre-Occupancy Evaluation" (Patkin 1991) where intended users can review simplified large-scale plans, as described below.

Architects, clients and hospital design

Architects are not trained specifically in hospital design and their biggest problem in designing ORs is knowing where to start. Typically narrow budgets, deadlines, and politics limit them. They are presented with a site constrained by physical boundaries, and then work inwards to fit in the various facilities requested. A more rational ergonomic approach is to start with the various tasks, define the consequent needs for space, and then work outwards to where walls will be placed. Somewhere and somehow these two approaches must meet and harmonize.

The clients of the architect are usually regarded as the funding body, but equally they should include the users of the facility. These are in many different groups and most will not meet the architect, but be represented by managers often remote from the work to be done. Those with the weakest voice are patients and junior staff, whose needs take time and effort to determine.

Generally some senior staff will take part in planning meetings. Typically these are the OR nurse manager, a senior anaesthetist (who may be called away frequently) and an administrator largely concerned with the budget. Contributions of other staff are brief and often difficult for them to formulate. If the hospital culture is an authoritarian one the views of junior staff, or other employees such as technicians, plumbers, electricians, cleaners and others will not be sought. Often it will seem quicker for architects to make arbitrary decisions There is an underlying problem of communication in the planning process, because suitable tools have not been used, though they exist and are simple to use. . The result is a facility that is less efficient, more costly, awkward and less satisfying to work in.

Three important tools for communication

There are three useful tools that can solve many of the problems of communication during the planning and design process. These are:

(1) a checklist of several hundred items for OR design (Patkin 1998),

(2) the planning handbook for the project which is updated as a continuous process, and

(3) an updated series of one to ten scale plans drawn on a faint 1 cm grid (or 1:12 on an inch grid for non-metric countries) (see below).

The planning handbook, maintained on a computer within the OR, area must be the responsibility of a competent technical writer with a user-friendly style, who may need to be specially employed from the start of the project.

Successive revisions are printed and available in the tea-rooms of the OR, and copies of relevant sections are given to staff working in the various specific areas. Fine detail should be directed to relevant technical staff rather than swamping the attention of the others involved. It should contain the following sections:

-

Statement of purpose, expanded into a framework for the design to be built.

-

Overall summary of areas

-

A detailed checklist for each area

-

Support services whether within or outside the OR, including for example pharmacy and instrument maintenance

-

Storage design and management for each area

-

Flowcharts for movement of patients, staff, equipment, resources and information

-

Flow plans for electricity, water, air, gases, temperature

-

Proposed staffing, management, and budget

-

Interactions with other departments, general and detailed, with descriptive flowcharts

-

Adaptability to changing needs and technology

Like other paper in bureaucracies, this is likely to be a waste unless leaders of the project are approachable and take a lead in discussing and sharing the project with their staff. Fortunately the process described is realistic and inexpensive using standard desktop computing and email.

Choices and Dilemmas

In planning a large complex nowadays there are some unresolved questions. Should theatres be grouped in separate pods for easier management and control, or will the extra distances make communication difficult and need more cleaning, more staff and expense? How segregated should clean and dirty flows be? (Most intra-operative infection is from the shed skin of staff.) How specialized should individual ORs be? (Shifting equipment takes time and risks damage). How will workloads change, such as the move from open aortic aneurysm surgery to endoluminal surgery? (There is less time needed in the OR but more space needed for imaging equipment.)

Making plans easy for non-architects to understand

Computer aided design (CAD) is a powerful tool but intimidates many non-specialists.

To complement CAD, a way of simplifying architects' plans for discussion

(contrasted with the separate needs of builders) has been described (Patkin

1991).

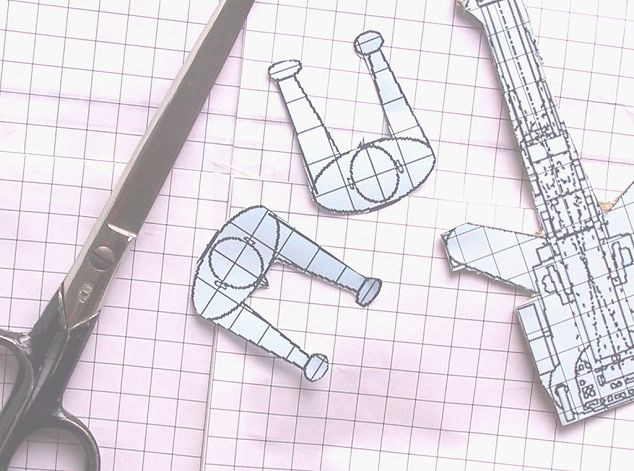

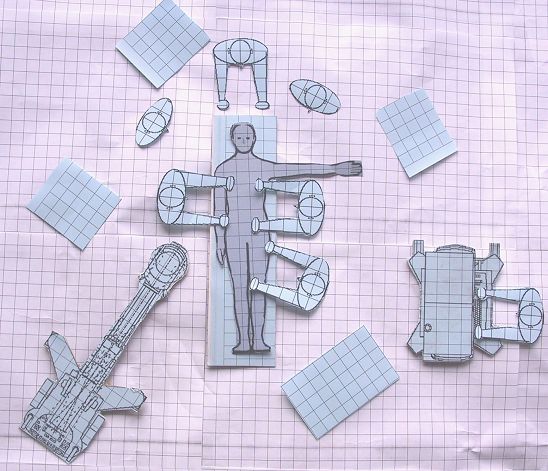

Plans are copied onto a 1 cm grid at a scale of 1:10, omitting all measurements. Cardboard cut-outs to scale represent fittings, movables, and people (2 x 4 cm for torso from above, head 1.5 x 2 cm and arms proportionately) using standard ergonomic diagrams (Sale 1980). The latest plan is kept in open view in the OR complex so every worker see it daily and discuss it with the project leaders.

Special requirements for the MIS (minimally invasive surgery) Operating Room

The main additional requirements for MIS are storage for video carts ("towers"), disposables, and other specialized equipment for specific procedures. Within the OR there should be hanging pendants for monitors, electrical supply, data cables, gases and suction, on mobile arms and cantilevered for adjustment of height. Bulky imaging equipment for x-ray and ultrasound should be accommodated, and in some cases equipment for intra-operative radio-, cryo-, and other emerging therapy. Procedural aids, training material, and documentation should be on hand with copies for staff to take away. A nearby simulation laboratory should allow practice, teaching and research of the difficult manipulations involved. MIS is an intensely visual activity, and video links for remote viewing and recording should be available for research, teaching, and quality control. A common problem in MIS is poor placement of monitors so that operators and assistants have to crane their necks upwards awkwardly, or have to re-orientate their eye-hand co-ordination.

Conclusion

OR design is full of problems, but answers to these are available as long as the planners are willing to go beyond the usual limited methods.

References

Patkin M (1991) Hospital Architecture - An Ergonomic Debacle. In: Estryn-Behar

M, Gadbois C, Pottier M, eds. Ergonomie a l'hopital, Colloque international

Paris juillet 1991. Octares Editions, Toulouse 1992. 79-83.

Patkin M. Checklist for OR Design. Document posted to the SURGINET Internet

listserver. 1998. Available by email from the author at mpatkin@camtech.net.au

Preiser WPE, Rabinowitz HZ, White ET. Post-occupancy evaluation. New York:

Van Nostrand Reinhold 1988.

Sale,K Humanscale. Secker and Warburg, London 1980.

-o0o-

Contents

Introduction

Architects, clients and hospital

design

Three important tools for communication

Choices and dilemmas

Special requirements for the

MIS OR

Conclusion

References

Summary

Adapting the modern operating room (OR) for minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is a challenge which begins with the more general problem of designing any OR. Apart from the scarcity of practical publications and details in this area, the reasons are the highly technical nature of many of the issues and the difficulty of communicating them, though often the mistakes made in planning are at a very simple level. Three specific ways of improving communication in planning are using a checklist, sharing a planning handbook among the intended users, and modifying architects' drawings to 1:10 scale floor plans with movable cut-outs to represent equipment and staff.

Operating room design for minimally invasive surgery

Michael Patkin

Clinical senior lecturer

Department of Surgery, Flinders University, South Australia

The gist of this paper was published in MITAT in 2003. I was asked to provide a paper ondesigning the new type of operating room appropriate to the era of Mimimally Invasive Surgery.

I turned this invitation on its head by saying the underlying problem, or challenge, was lack of an accepted way of designing any sort of operating room. So this became the subject of my paper.

I made seveeral mistakes in it. The first one was to treat it as an armchair exercise, because I had no practical experience, and was only to get some late in 1994, when I was asked by Guy Maddern, at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital, to join the group of people responsible for designing a nw suite of operating theatres at that hospital.

The second mistake was that I considered only the operating room iteslef, and not the whole suite of subdepartments and room that make up a surgical opeerating complex. See elsewhere for the final result, which was still under way when this website was launched.

However I think the information here will still be of great help to people engaged in this challenge.

-o0o-