This chapter describes a study of neck and arm pain among operators of video display units (VDUs) and others doing repetitive work in a small industrial city in South Australia and is a combination of medical and ergonomic analyses.

Apart from neck and arm pains, other common health complaints among VDU operators are eyestrain, concern about miscarriage and foetal abnormalities and facial rashes. Controversy about all of these is aggravated by several factors:

1. conflict between employers and employees,

2. lack of trust by employees, based on past hazards

3. threat to job security of new technology, and

4. lack of medical knowledge and poor results of treatment.

Emphasis has varied from one country to another, for example neck and shoulder problems in Scandinavia and Japan, concerns about eye damage and radiation risks to pregnancy in the United States, musculoskeletal conditions in Australia, and until recently little public awareness of any problems in the UK. As information is shared internationally, these distinctions are disappearing.

The Australian experience has been instructive. The terms tenosynovitis, repetition strain injury (RSI), and overuse syndrome were used at different times to refer to complaints among process workers and typists developing severe or intractable pain and weakness in the arms and hands attributed to their work.

Doctors in Australia faced an epidemic of RSI in the early 1980s which they were not trained to cope with, and their role of authority was transferred to ergonomists and to other health professionals. These in turn had temporary success by correcting obvious ergonomic deficiencies, partly through the usual placebo effect, and also because these groups opened up communication between managers and employees. Professional leadership then passed to rehabilitation services. Since then, State government programmes of rehabilitation have cost billions of dollars in their first few years. Much of this cost has gone towards treating chronic pain syndromes - conditions where pain persists in the absence of physical explanation, aching arising from normal muscle use, or exaggerated symptoms from muscle strains that would otherwise have been regarded as less significant. However, effectiveness of programmes in terms of return to work is improving, and fortunately the incidence of reported new cases also appears to be declining.

During this time various models of the 'RSI phenomenon' were developed (Wright, 1987). They included a wide range of social and psychological factors as well as medical and ergonomic ones. However, they failed to explain many of the problems of neck and arm pain, and new theories about their causes have emerged to challenge them.

This chapter describes four aspects of neck and arm pain at work whose details have received too little attention in medical and ergonomic models. These are muscle tension, hand position, neck posture and rehabilitation.

The normal amount of muscle activity needed for movement or control of posture is exceeded in several circumstances:

1. Tense habits of work - People have different individual patterns of muscle activity, seen in a wide range of activities such as handwriting, walking, talking, music and golf. These differences include poor timing of acceleration and speed of movement, and not exerting the right amount of force. If this force is excessive through 'trying too hard', there is more than normal muscle fatigue and ache. Often this occurs with haste, anxiety or anger.

2. Co-contraction - Muscles seldom contract on their own without contraction

of opposing muscle groups; these correct slight errors in speed or direction

through gentle braking, similar to the small adjusting movements of a

steering wheel.

'Co-contraction' is isometric contraction of active and opposing muscles

(agonists and antagonists) at the same time when it is excessive. It can

be demonstrated by putting the hand into an aggressive clawing position

and seeing or feeling the hardness of the muscles of the forearm. Severe

and continued co-contraction will cause pain which may be confused with

an obvious medical condition such as carpal tunnel syndrome or tenosynovitis,

especially when combined with poor wrist posture (see next section).

3. Excess demands - Caused by, for example, heavy levers or stiff controls, this factor is well known in ergonomic practice, but excessively stiff keys or badly maintained controls can still be found.

Strong actions by the fingers are carried out by the powerful muscles of the forearm, which curl the fingers into a fist. More rapid, but weaker, actions are carried out by the small intrinsic muscles of the hand, which work best with the fingers bent at their base but less curled along their length. Modern electronic keyboards require a light touch, much less than for older manual machines, and therefore a straighter position of the wrist, rather than the dorsiflexed posture which favours more powerful movements by the heavier and slower muscles of the forearm used for more powerful grips and movements.

Some typists dorsiflex their wrists severely, or angle the hands outwards. To maintain these positions, the muscles which bend the wrist backwards or towards the side of the little finger, which take origin from the outer side of the elbow, must contract much more than normal.

Discomfort in the neck and arm is often due to a poked-forward position of the head. Such posture can be caused by glasses with too short a focal length. The mechanism of pain is probably excess tension in the nerves of the arm, like that of sciatica, when disorders of the lumbar spine cause pain in the leg.

There is a higher incidence of musculoskeletal pain, as well as accidents, when people are just back from holiday, or when the workload has suddenly increased. Even when the job design and style of work have been reviewed, experience shows that people re-starting work after an injury or accident need to begin with a much lighter schedule. This is gradually increased to normal over a period of days or weeks.

The data presented in this paper consist of observations on 133 individuals, all those seen between 1982 and 1988 with work-related pain in the arm and neck in the private practice of a surgeon with a long background in ergonomics. These cases were referred as patients from other doctors, as clients of lawyers, and in a few cases as employees directly from their workplace.

There were 35 cases, or approximately one quarter, whose symptoms were directly related to work with VDT terminals, and another smaller number of clerical workers with problems from handwriting. The remaining cases covered a wide range of occupations, but with important characteristics in common.

Most patients came from Whyalla, a steel-making city of 28 000 people situated in a sparsely populated, arid area 400 km by road from Adelaide, the state capital. Some patients were referred from Port Augusta, a small city 1 h away by car. Others came from small country towns in a radius up to 600 km, or were flown from Adelaide for medico-legal assessment, or reviewed in Adelaide itself.

During the same 6 years approximately 4500 other patients were treated, so that the group under study constituted 3% of the total. A former telegraphist and a patient aged 81 who are discussed below are not counted as part of the series.

In early cases only a brief history was recorded, and much of the information desired later was not available. At the start of the study, cases of disabling pain associated with office work appeared as ergonomically interesting but not especially significant. Only as the study progressed did the significance of such cases emerge as part of a huge and expensive national epidemic.

Records were reviewed retrospectively in 1985, after 76 cases had been seen, and again in February 1988, when there had been 133 cases. A further 10 new cases seen by the time of writing are not included here. (Measurements of force in this study are recorded in Newtons; 1N is approximately equal to 100 g weight, or just over 3 oz. An American 5-cent piece, or 'nickel', and an Australian 10-cent piece each weigh about 5-5g.)

Observations on the first 75 cases were presented to a state meeting

of the Australian Physiotherapy Association in 1985, under the title of

A Muddled Label. Each case was summarized in 40 words or less. Key expressions

were then used to classify them into 17 descriptive groupings or clusters

(Table 13.1).

Table 13.1. Descriptive groupings,first 75 cases.

|

The nine cases in the subgroup of distorted symptoms (12%) are listed individually (Table 13.2). They were cases where there was no connection evident between the stated cause and the long-standing pain. They were important to identify as early as possible, because they were difficult or impossible to help medically, and they gave other cases a bad name.

13.2. Distorted symptoms.

|

Three cases labelled 'ergonomic success' are described in more detail (Table 13.3). Each of these had chronic pain cured by ergonomic analysis and alteration of their activity. Normally two of them would otherwise have undergone surgery in an attempt at cure.

Table 13.3. Ergonomic cures.

|

Cause

|

Mechanism

|

Cure

|

| Writing too hard | Habit, stale carbon paper | Fountain pen |

| Poor supervision | Bent neck | New glasses, desk |

| Kneading dough | Bent wrists, age 81 | New hobby |

Case 1. Writing too hard

The 40-year-old female manager of a fashion boutique had a classical De Quervain's tenosynovitis of the right wrist, with symptoms for 2 years despite physiotherapy and anti-inflammatory drugs. When she was referred for surgery, there were typical swelling and crepitus which left no doubt about the diagnosis. However examination of her handwriting style showed that she pressed very hard with a pen. She was prescribed a fountain pen, lost all her symptoms in 5 days, and had no need of surgery.

Follow-up examination at her shop showed she wrote dockets for 1.5 h per day using stale carbon paper. When writing she pressed with a force of 6 N. This was measured on a Chatillon push-pull gauge mounted immediately next to her desk, with her hand supported in the usual way. After she started using a fountain pen, the force reduced to 1.5 N. This was still excessive, as the minimum force required to write with a fountain pen is less than 0.01 N (under 1 g weight). There was a family joke that her husband was able to hear her writing across the other side of their thickly carpeted living room.

Case 2. Failure of supervision

A 50-year-old female clerk at my hospital was off work for 6 months because of neck pain. Ten years earlier she had a cervical laminectomy and fusion for spondylosis. In the previous year she had been seen by over a dozen doctors, including two neurosurgeons, and two orthopaedic surgeons on behalf of an insurance company. Though her general health was otherwise good, she was unable to do her housework and had no social life.

Her job consisted of copying numbers from a book of medical benefits fees to accounting forms. An ergonomic examination of her workplace showed she was hunching forward to work, and the office arrangements had at least seven faults:

1. desk too low,

2. chair not adjustable,

3. source documents fiat on table,

4. writing surface flat instead of sloping,

5. inadequate lighting

6. reading glasses focused too close, and

7. lack of supervision of her working posture.

A report of these faults was ignored by management for several months, and she was off work most of this time on compensation payments. In the meantime her husband, a technician, made an adjustable board to support the documents she was reading and writing on, and her desk and chair were replaced with adjustable ones. She returned to normal work after this.

Follow-up 1 year later showed she was now quite free of symptoms, and her personal and social life had improved remarkably. Sad to relate, 2 years after successful rehabilitation her job was computerized with no ergonomic supervision of the changeover. Within a few days her old neck problem had recurred because of poor workstation design and bad neck posture. She was off work for 2 months because of further symptoms and then retired permanently on an invalid pension.

Case 3. Not kneading the dough

An 81-year-old female, mentioned earlier, was referred with clear-cut symptoms of bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome for 1 year with typical distribution of night pain. On taking a detailed history, it emerged that she had taken up home bread-making as a hobby shortly before her symptoms began. When she mimed the movements of kneading the dough, it became clear she dorsiflexed her wrists forcibly. After she gave up her hobby, with regret, she was pleased to find her symptoms disappeared within a few days.

With increasing experience with the first 76 cases, a more detailed history and examination were recorded for later patients. Towards the end of the study, a data base was created on a personal computer using dBASE3, with 26 fields for each case record. Six fields had clinically less relevant information (number, name, date, doctors and solicitors involved, and employer) leaving 20 fields with clinically relevant information (Table 13.4).

Table 13.4. Clinical information.

| 3. Age 6. Job title 7. Likely ergonomic factor 8. Past history 9. Symptoms 10. Complaint of swelling 11.Duration 12. Stated disabilities 13. Exaggerated disability 14. Signs (general) |

15. Hypoaesthesia 16. Brachial plexus test 17. Co-contraction 18. Psychological factors 19. Diagnoses 20. Management 23. Outcome 24. Comment 25. Organic or functional 26. Notes |

At first this tabulation was a clumsy tool for analysing data because

the study was retrospective. The history had not included many of these

items, and criteria for them had not been defined at the start. A study

of individual factors sometimes required creation of an additional field,

manual transfer of data from other fields, and review of all the records

in the series one by one. This was done several times. These categories

will be revised for future studies.

In some other respects the direct manipulation of the data base became a particularly useful tool. A standard terminology evolved by repeatedly browsing through records in an alphabetical order for the factor under review and altering inconsistent terminology, and some information was extracted by highlighting particular records in the printout.

There were 30 cases seen only once. Reasons for this were that their complaint was minor and easy to resolve, they had been referred only for medico-legal assessment, the patient chose not to return for further treatment, or they had been advised management elsewhere. -

There were 103 cases reviewed on more than one occasion, and many of these were seen between 5 and 10 times to monitor their course and management.

The main occupational groups were office workers (45), factory workers (38), and service workers in food, cleaning and sales (30). Others were switchboard operators, music teachers or students, and miscellaneous (Table 13.5).

Table 13.5. Occupational groupings.

|

These results were reported briefly at the recent International Ergonomic Congress in Sydney (Patkin, 1988a).

The cases in whom excess muscle tension was detected were office workers, cleaners and a labourer. While the main stated cause for pain among office workers was keyboard work in 35 cases, there was also a group of 10 cases who considered the cause of their problem was handwriting at work.

Tense habits of work were assessed on criteria which were added to as the study proceeded. These now comprise general habitus, handwriting faults, and other movements at work.

The arm movement of subjects was observed as they walked into the examination room. They were asked to swing their arm loosely and then observed for free movement of the elbow and wrist. The subject's forearm was supported loosely, and then allowed to fall under its own weight. Subjects were considered tense if the arm stayed momentarily in position before falling.

1. Pressing too hard with the pen - This was assessed by having the subject write on ordinary paper rested on a folded handkerchief. If the subject pressed too hard, the paper was indented, and this was evident on looking at and feeling the other side of the paper. The greater the force, the more severely was the paper indented, and in some cases it was actually torn.

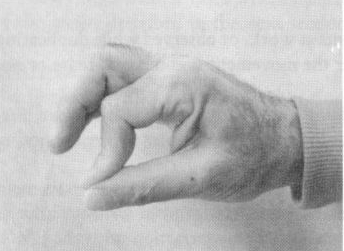

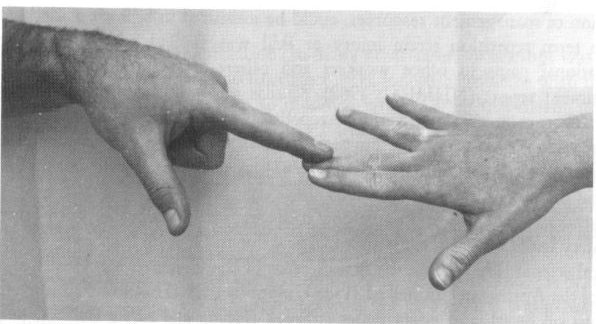

2. Gripping the pen too hard - The index finger-tip was bent back passively and the skin blanched over the back of the interphalangeal joint. Figure 13.1 contrasts the index finger posture of a forceful pen grip [Figure 13.1(a)] with the superior posture of a relaxed grip [Figure 13.1(b)].

3. Co-contraction - This was manifest when the extensor muscles of the forearm were contracting too firmly. This could be felt, and in thinner subjects could also be seen.

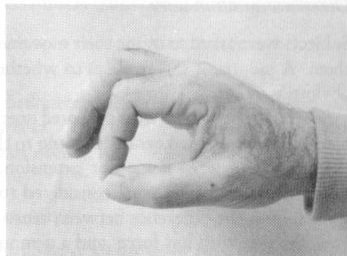

A pocket electromyograph (EMG) made by Group Occupational Health Services

of Sydney was also used to demonstrate this, and made it much easier to

explain to the subject what the problem was. This device was attached

to three surface electrodes on the subject's forearm, of which two were

a few centimetres apart over the line of the extensor muscles under test,

and the third was an indifferent electrode a little away from this line

(Figure 13.2). Ingenious and compact circuit design resulted in bleeping

when muscle tissue contracted, and the pitch and frequency of the bleeps

increased as the muscle activity increased. The small size, freedom from

extraneous signals, and reliability of the EMG made it an impressive and

effective tool both for diagnosis and understanding by the subjects.

Figure 13.1. (a) Forceful and (b) relaxed pen

grip postures (reproduced with permission from Modern Medicine of Australia).

Figure 13.2. A popular Australian, pocket-sized, EMG and electrode siting.

Subjects were asked to mime their movements at work, or observed while duplicating them. A judgment was made as to whether the movement was relaxed, tense or not obviously either.

Several of the typists were observed operating a keyboard. A note was

made of how hard they pressed the keys by listening to the loudness of

the impact, as well as noting their degree of wrist flexion or extension.

Those subjects who were considered to have tense patterns of muscle movement

were shown the difference between tense and relaxed handgrips in writing,

how to press the pen with less force, and a demonstration of co-contraction

with the EMG. Some typists were given a trial of EMG to show them the

effect of varying wrist posture on muscle activity.

Office workers who wrote a lot and had tense 'writing habits were told which brands of pen wrote most easily. A separate study was carried out of 23 different models of ball-point pen writing on paper supported on cloth, as described earlier. Measurements were made of how much force was needed to write legibly (0.03-0.25 N), to indent paper (over 0.2 N), to tear it (over 0.6N), and to make legible carbon copies (variable). Fountain pens write with under 0.01 N. Some brands of ball-point pens now available write consistently with a force of less than 0.04 N.

Office workers with excess tension

There were 37 cases of office workers using excessive force when typing or writing, according to the criteria above. Only 22 cases out of the 37 were followed up adequately. Most of these improved with simple advice (Table 13.6).

Table 13.6. Results of treating excess muscle

tension (including dorsiflexion) in office workers.

|

Activity

|

Number

|

Followed up

|

Improved

|

Not improved`

|

|

Keyboard

|

27

|

13

|

7

|

6

|

|

Writing

|

10

|

9

|

8

|

1

|

Among the 35 keyboard workers in this study, eight had neck pain as the leading r symptom. and 27 complained mainly of arm or hand pain. Among the latter group, 14 were seen only once, leaving 13 cases with hand and arm pain treated and followed up. Of these 13 cases, seven were cured by simple advice to buy better-quality ball-point pens and to grip and press with less force. It is likely that several of the cases seen only once also recovered. Of the six cases which failed to improve with simple advice, four were involved in protracted litigation or had disputes at work, or had significant psychological problems; and the other two had significant psychological problems in their personal life.

These results include cases where the excess muscle tension was due to dorsiflexion of the wrist, described in the next section.

All 10 clerks with pain from handwriting had a tense technique. Of this group, all except two lost their symptoms in 1 or 2 weeks. One was not followed up, and the other was angry with his employer over past events.

Results of treating non-office workers with excess tension

Isolated cases of muscle pain associated with excess strain were seen in four other activities - cleaning with electric floor-polishers, hammering, morse-code operation, and music - as well as the amateur breadmaker described earlier. The numbers are too small to have significance, but analysis of their activities appears to support the general thesis in this section.

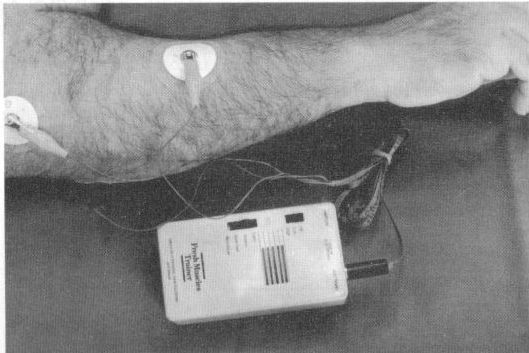

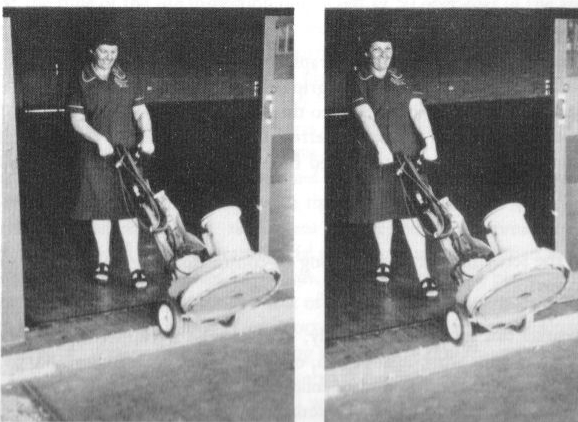

There were two cases of lateral epicondylitis in this group. A work-site inspection showed that both had occurred in cleaners who pulled a heavy commercial polishing machine up a step because there was no sloping ramp for them to use.

Their supervisor, who had no problems of arm strain, had a technique of pulling the machine up the step by keeping the elbow straight and balancing the machine with her body weight (Figure 13.3). This allowed the extensor muscles of the forearm to stay relaxed.

Figure 13.3. Two ways of pulling a heavy polisher up steps.

Simple observation of the arm action required shows that if it was carried out with the elbow slightly bent, it requires strong contraction of the forearm extensors attached to the lateral epicondyle. It is easy for the seated reader to confirm this phenomenon by pulling on the edge of the seat, while palpating the extensor muscles of the forearm with the other hand, first with the elbow straight and relaxed, then with it bent.

There is a second risk factor related to skill for cleaners using floor polishers. Normally the rotating head of the polisher is kept nearly flat on the floor. Tipping the polisher gently towards and away from the operator makes it move to the left and right in turn, giving arcs of movement across the floor. Tipping it slightly to one side and then the other at the end of each arc gives a more graceful and easier figure-ofeight movement. If the operator tips the machine too much, it means she has to "fight" the polisher and grip it more fiercely.

Both of the cases in this series were involved in litigation, and in neither case did the symptoms improve over many months. A third cleaner, who also failed to improve over several months, had the habit of holding the wrist flexed all the time. If she held a shopping bag, it took extra effort to keep it out of the line of gravity. She held the wrist flexed severely, whether holding a broom or a shopping bag.

There was one case of a male ex-clerk aged 36, who developed pain in both forearms while cleaning tough grease from inside a large furnace with a chipping hammer. When asked to mime the technique he used, he pushed the hammer by extending the elbow with a short stroke and a stiff arm, instead of swinging in a loose movement from the shoulder joint.

At a local historic demonstration of telegraphy, two former operators showed distinct styles of hand-grip. The operator with a grip tense enough to hyper-extend the tips of the index and middle finger-tip [similar to the posture shown in Figure 13.1(a)] used to suffer with forearm pain at work, referred to as 'glass forearm' or 'telegraphists' cramp'. The operator with gently curled fingers [similar to the posture shown in Figure 13.1(b)] had no such pain.

All four in the series had unusually strong co-contraction when their handwriting style was tested.

To summarize this group, in this study, 15 cases who were followed up

out of a series of 133 cases with work-related pain, or 11%, gained relief

by learning to relax their habits of work. The incomplete follow-up means

this success rate has been underestimated, but many cases also demonstrated

tension of nerves in the neck and arm (see next section), so no conclusions

can be drawn about the significance of muscle tension on its own.

As mentioned earlier, subjects had been asked to mime the action of typing, and then observed while actually typing. Wrist posture was considered faulty if there was dorsiflexion of the wrist beyond the neutral position, or if there was more than minimal ulnar deviation of the wrist.

Although observed on only a few occasions, every case in which the wrist was dorsiflexed when typing showed increased muscle tension compared with that when the wrist was straightened. This was obvious on palpating the extensor muscles of the wrist, either by the examiner or the subject's other hand, and in a few cases on using the pocket EMG. The outcome in these cases has been incorporated in the data for 'excess tension' in the previous section.

Similar excess muscle tension could be demonstrated if the wrist was deviated to the ulnar (little finger) side, either because the keyboard was to one side (e.g. to make room for a document holder), or habit, or because the subject had a wide trunk; so that the forearm was at an acute angle to the keyboard instead of a right angle.

One related phenomenon was seen at an office among a group of keyboard

workers at a large remote worksite, whose data were not included in this

series. The accounting system used had recently been converted from a

manual system to a computer-based one. Of 50 operators, 11 had begun to

complain of forearm pains similar to those described earlier within a

few weeks of starting to operate keyboards.

In this system, all alphabetical fields were entered in upper case. To

save using the numeric pad, the shift lock key could be operated to reassign

ten of the alpha keys temporarily for numeric entry, and operated a second

time to enter the numeric field. This key was at the extreme right end

of the keyboard and operated by the little finger. At the time of the

site inspection only 2 out of 50 operators in the area were entering data.

However two quite different techniques of operating the key could be seen

from as far as 5 m away. Using the 'forearm shift' technique, the operator

moved the whole forearm to the side, like a pianist playing, to position

the little finger over the shift lock key. In the 'little finger stretch'

technique, the forearm moved less or hardly at all, and instead the little

finger was stretched sideways.

It appeared likely that the second style was the one used by those complaining of pain. Testing muscle tension by palpation and by EMG confirmed the excess muscle tension on the outside of the forearm with the 'little finger stretch' technique.

Prior to the inspection and subsequent report with recommendations for supervision of keyboard technique as an initial step, the employees' union had pressed for redesign and supply of modified keyboards, with the return key placed next to the alpha keys. The supplier had quoted a cost of A$100 000 for this modification.

Observations and discussion with operators at the time suggested the alteration in typing technique could be effective in solving the problem. Follow-up on this group was not available, but its success seemed likely on the basis that the operators could understand the cause of their new pain and what they could do to prevent it.

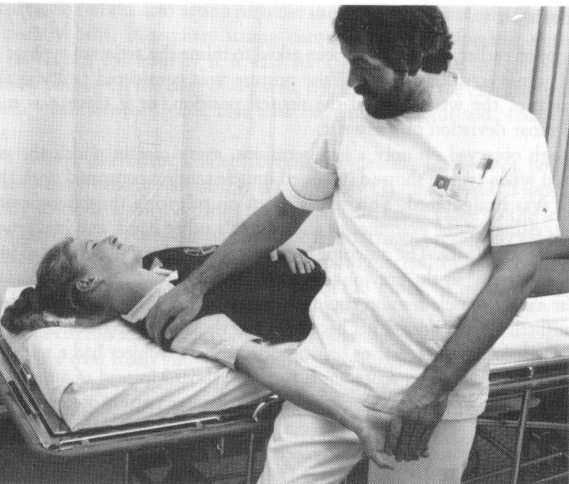

It was only in the latter part of the series that a test was included

for brachial plexus tension (BPTT). This test was devised by Elvey (1979),

a physiotherapist in Western Australia, in 1979. In this test the large

nerves of the brachial plexus are stretched by putting the arm in a suitable

position. This is similar to stretching of the sciatic nerve in the well-known

straight-leg raising test, a common clinical test for lumbar spinal 'Physiological,

production of aching or tingling in a different area

causes of pain in the leg. to the one in which the symptoms had been reported.

The version of the BPTT used here was simplified from the version devised by Elvey (Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4. Brachial plexus tension test - one of several steps (reproduced with permission from Modern Medicine of Australia).

The steps are as follows

1. The subject lies flat on the back on an examination couch. symptoms

to their neck posture so that they were able to understand it

2. The head and neck are bent (not turned) to the side away from the examiner.

3. With the subject's shoulder out to a right angle, the examiner holds

the subject's forearm with the palm outwards (supinated), straightens

the elbow, and steadies the upper arm against the examiner's thigh.

4. The examiner pushes the patient's shoulder down towards the feet.

Each of these steps applies tension to the nerves of the arm along their whole length, a fact which becomes obvious if these manoeuvres are carried out when these nerves are exposed at operation.

The BPTT is positive if it reproduces the pain and tingling in the site usually noticed by the patient in relation to work. These symptoms should disappear when the patient's shoulder is allowed to elevate to its relaxed position. The commonest site where symptoms are felt is over the 'extensor pad'. (This refers to the prominent muscular area a few centimetres below the outside of the elbow.) In some patients these symptoms occur at the front or back of the wrist.

This test may be positive in one or both arms. There is also an incidence of false positive or 'physiological' results. In normal people it is often possible to produce similar tingling and discomfort in some part of the arm, but when the site is the same as that of work-related symptoms the pains are likely to respond to the simple treatment measures outlined later in this chapter.

Elvey now distinguishes between different parts of the brachial plexus and different nerve trunks by flexing the elbow (which relaxes the median nerve but tenses the ulnar nerve), adjusting neck position, and other manoeuvres which were not included in this series (R. L. Elvey, personal communication).

This test was only carried out in 54 cases in the latter part of the series after it had become known to the author. It was also omitted in a few later cases where it was clearly not relevant, or where the subject happened to be seen at the worksite and suitable examination facilities were not available (Table 13.7).

Table 13.7. Findings using the BPTT.

|

*Physiological, production of aching or tingling in a different area

to the one in which the symptoms had been reported.

:

The management of those cases with neck pain was to demonstrate the relationship

of their arm symptoms to their neck posture so they were able to understand

it clearly, and then to advise them on neck posture, neck exercises, and

where appropriate the need for glasses of longer focal length. Some patients

were referred for manipulative treatment.

Of the 31 subjects in whom the test was positive, 16 were known not to have gained relief during the period of the study. There were eight cases where the outcome was favourable, and seven in whom the outcome was not known. The favourable results occurred where subjects followed advice to avoid slumping their neck and to carry out neck retraction exercises (McKenzie, 1983) as discussed below.

Of the nine subjects in whom the BPTT was negative, one was not followed up, four improved, and four did not.

Many of the cases also had evidence of excess muscle tension, as listed earlier. The overlap between these two factors means it is not possible to assign significance to them individually.

Simple cases had no formal rehabilitation. In many other cases, an attempt was made to contact the employer with a view to correcting ergonomic problems with the job and allowing the employee to return to modified work. Often this meant starting with 2h per day and increasing to a full day's work over several weeks.

In later cases, job design was assessed by ergonomists from an outside rehabilitation service, to which patients were referred if they were not making good progress.

There were 30 cases seen only once. Of the remaining 103 cases, 40 appeared to achieve complete relief, 50 were unchanged or worse, five improved partly, and the outcome was not clear or unknown in eight cases (Table 13.8).

Table 13.8. Duration of symptoms when first seen versus outcome.

| Duration | Relief | Partial | None | Unknown | Total |

| <lm | 9 | 1 | 2 | - | 12 |

| 1-2 m | 12 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 24 |

| 3-12 m | 10 | 3 | 19 | 3 | 35 |

| >12m | 9 | - | 20 | 3 | 32 |

| Total | 40 | 5 | 50 | 8 | 103 |

Much of the motivation for this study arose from the author's frustration

in attempting to diagnose and treat increasing numbers of patients referred

with work-related symptoms which did not fit into current medical models.

Some of the interest in these problems developed from earlier observations

on the nature of skilled hand function. A further stimulus to work in

this area was the serious and growing public controversy and the escalating

costs in working time and diversion of resources to deal with it.

Complaints of pain. among VDU operators and others doing repetitive work have been costly in both human and financial terms. In Australia the cost to the economy, including direct working time, compensation to emplovees, advisory services, and diversion of management resources, could be measured in billions of dollars.

The term repetition strain injury or RSI was applied widely in Australia to occupational pains in office workers and others after its first appearance in a government report (NHMRC, 1982). Similar terms used earlier were 'repetition injury' (Ferguson, 1971) and muscle repetition injury (Taylor et al., 1981). Its use became widespread in the next few years. Its history as a social phenomenon has been reviewed in detail (Spillane and Deves, 1987), as well as its recent decline in a large national organization (Hocking, 1989),

Australian awareness of occupational pains and strains, together with other health and safety issues at work, came about largely due to Dr John Mathews, a graduate in political science. He became the first director of the Occupational Health and Safety Unit of the Australian Council of Trade Unions in 1981. This unit published frequent bulletins on health and safety issues at work (Health and Safety Bulletin, periodical) which had wide circulation and great influence. Mathews was a competent analyst, publicist and writer (Mathews, 1985), but his political commitment at times appeared to outrun the scientific data.

As a result of the influence of Mathews and others, tenosynovitis was frequently diagnosed in factory process workers and typists. Young women wearing forearm splints became a common sight in medical and paramedical waiting rooms, in newspaper photographs and occasionally in city streets. It became clear that this diagnosis was wrong in nearly all cases. The epidemic of reported RSI cases in Australia was a regular feature in the national media and then appeared to become less fashionable.

A vigorous debate developed between the proponents of two views 'it's all in the head' versus 'it's all in the body'. Doctors became caught up in the same bitter debate, with diagnoses such as conversion hysteria on one side and 'overuse injury of muscles' on the other. Numerous theories appeared to explain the epidemic, including fluoridation, neck problems, muscle tension, malingering and psychogenic pain.

Each of these views had supporters who excluded all other viewpoints. They ignored emerging factors such as congenital ligamentous laxity, carpal bone instability, previous injury to the neck or fracture of the forearm (even in childhood), and co-incidental specific problems such as capsulitis of the shoulder and lateral epicondylitis, either arising spontaneously or from identifiable causes.

The diagnosis of common conditions was sometimes missed by doctors irritated by increasing numbers of patients, often self-referred with a diagnosis of RSI, so that simple tests for definable injuries such as lateral epicondylitis - lateral elbow pain on resisted extension of one or more of the central digits (Figure 13.5) - were not carried out. A fresh clinical approach to individual patients was needed (Patkin, 1988b).

It gradually became clearer that RSI, overuse syndrome and similar expressions were unsatisfactory. They were confusing and damaging umbrella terms which refer to a wide range of different conditions. Their common features were pain related or attributed to work, but like other medical and social entities there is a central group of shared features whose different patterns made rigid definition a problem.

Figure 13.5. Simple test for lateral epicondylitis

(reproduced with permission from Modern Medicine of Australia).

The very choice of terminology became a prejudgment, an expression of viewpoint or prejudice. If a person with professional authority uses the term 'injury' in this context, this is likely to be understood as implying a physical disruption or displacement (by contrast with 'injured feelings'). If a neutral term like 'complaint' or 'pain' is substituted, there is more likely to be the belief or understanding that there is some temporary and quickly reversible condition.

Against this confusing background, the purpose of this current report

is to draw attention to specific physical factors which have been neglected

in the past. Great attention has been given to details of seating, screen

characteristics and other ergonomic factors, but the factors considered

here seem to have fallen into a gap between medicine and ergonomics.

Regrettably this retrospective study does not distinguish between the

roles of the different factors analysed as clearly as was hoped initially.

It is an everyday observation that individuals vary in the pattern of their muscle movements, e.g. in walking, handwriting, speech, sport, music and work. Poor skill at work has received scanty recognition in theory or practice. A case of tenosynovitis in a shoe assembler, probably due to excessive force, was mentioned by Welch (1973).

Nine cases of work pain from tense habits associated with poor skill

were recorded under the label of 'trying too hard' (Patkin, 1984).

Earlier observers of cramp in writers and telegraphists considered it

was due to involuntary muscular contraction (Gowers, 1888). However subjects

in this series were able to learn a more relaxed writing style using the

techniques described. In sport and music it is common to re-train skilled

movements to be more relaxed and efficient.

This ability to relax muscles not needed for the action is seen in videotapes of competitive downhill skiers, when the hamstring muscles (at the back of the thigh) are not needed to maintain knee stability and can be seen to relax, and in the triceps muscle of a cellist who is making a confident 'ballistic' bowing movement.

Another aspect of strain and excess muscle tension is 'timing', a term which does not appear to have been defined in the ergonomic literature. Good timing is the rate of application of force which maximizes the transfer of energy. An example is pushing on a child's swing when it is moving away from the pusher. A second example is using a hammer, accelerating its movement steadily instead of with a jerk at the start, which appears to have been the mechanism in the 'hammering' case described earlier.

Timing also includes the sequence in which different muscle fibres contribute to an action. This is seen in competitive weight-lifting, when the muscles of the back come into play with their slower initial acceleration before those of the quadriceps in front of the thigh.

An area of great interest for testing this concept is doubtless that of manual handling and the prevention of back injuries, when taken in conjunction with other factors already recognized.

Further aspects - EMG, equipment, maintenance, anger

Undoubtedly the development of portable inexpensive EMG machines has been a major factor in clarifying the role of excess strain, and should prove invaluable in retraining keyboard operators and workers in other areas.

Some of the blame for bad skills and bad writing habits can be put on manufacturers of ball-point pens of poor quality which need more force for the ink to flow. Even if the ink flow fails only occasionally, writers get into the habit of pressing harder all the time in order to try and forestall this. Another factor may be the changing activities of schoolchildren. Poor motor skills, including handwriting, may be partly the result of spending their time watching television and playing with toys operated by punching simple controls, instead of hobbies requiring delicate hand activity, and playground games which develop fine motor co-ordination and timing (Patkin, 1987).

Skill includes much more than efficient patterns of muscle movement. It is also how people choose their posture at work within the range of constraints, what equipment they choose, and how they maintain it. 'The time-served craftsman has the ability to accomplish a whole repertory of tasks, and to determine the means for achieving them.' (Seymour, 1966).

In factory work the choice of equipment and how well it is maintained is outside the control of the operator. However while stiff controls on machines are well known to ergonomists as a cause of muscle load and strain, they are rarely a problem with keyboards. The ISO recommendation (ISO, 1971) of a key stiffness in the range of 0.25-1.25N is clearly too broad, and most keys require a force of 0.6-0.9N to operate, in line with recent studies (Grieg and Caple, 1986). Nearly all commercially available keyboards now fulfil this requirement, but some numeric keypads used for rapid data entry still require a force well over 2 N to operate.

Such levels of force exerted by the fingers are surprisingly not a problem in the apparently delicate work of pressing on the strings of a violin, where they have been estimated to be in the range of 0.5-1.5N (Basler and Kawaletz,1943).

One factor noted but not analysed in this series is anger. It is an everyday observation that some angry people become physically tense, for example in their body posture, when speaking, writing, pressing an elevator button, or operating controls. If anger causes pain (rather than the other way around), it will obviously be important to manage as a primary factor.

The traditional wrist posture for typists, dorsiflexion, was discussed in the introductory section. It was analogous to the power grip of the hand, which is much weaker if the wrist is straight or flexed. Like bad neck posture discussed immediately below, bad wrist posture may be due to bad training or habit, or poor design of the workstation. However, it has more in common with the tense habits of work discussed above. Both are examples of pain from excessive muscle activity rather than pain from tension on arm nerves.

Favourable data are accumulating following several ventures to redesign the traditional keyboard to avoid ulnar deviation of the wrist (Malt, 1977; Grandjean et al., 1985; Rose, 1986). It is probably too early for their wider acceptance. In a new development which extends the concept of wrist rests for typists, Stack (1988a, b) has argued strongly for slanting the keyboard away from the operator, which also flattens the wrist and the fingers. She asserts that this has been a major factor in solving the problems of RSI in the public service in Tasmania.

Although the importance of not flexing the wrist for rapid runs on the piano is well known to pianists, such skill factors are not taken into account by observers who claim there are microscopically visible changes in tissues in overuse syndrome (Dennett and Fry, 1988) and who rely on a controversial prescription of 'radical rest' for 'healing'.

While many keyboard characteristics have been studied in the past (Cakir et al., 1980) one not yet analysed is the effect of lack of resilience of the electronic keys. This imposes a sudden stop to the movement of the fingers which is transmitted to the forearm if the fingers are curled rather than straight.

Pain caused by neck problems is common.

At any given time, as many as 9 percent of the adult male and 12 percent of the adult female population is experiencing some discomfort in the neck with or without associated arm pain, and 35 percent of us can recall having such an episode. (Hult, 1954)

Figure 13.6. Neck exercise: (a) retraction, (b) protraction, to relieve brachial plexus tension (reproduced with permission from Modern Medicine of Australia).

Understanding of neck problems is poor, and they are not taught well to medical students. Advice is available in conventional medical textbooks, from doctors taking a non-orthopaedic approach such as Cyriax, rheumatologists such as Hadler, and many others.

The approach in this series has been to look for the simple remedial factors described earlier. The exercises advised for neck problems included especially retraction [pulling the neck backwards while keeping the head erect Figure 13.6(a)] and protraction [Figure 13.6(b)] for several seconds every few minutes or hours during the day. Patients were advised to buy a copy of a simple self-help book (McKenzie, 1983).

Other advice was to sleep with a low pillow, and to attempt to maintain a neutral neck posture. If simple measures did not solve the problem, then appropriate further help was sought, from professionals such as a rheumatologist, chiropractor, masseur or psychiatrist.

Formal rehabilitation services were set up in Australia approximately 20 years ago. They were largely organized along traditional medical lines rather than common vocational ones. With the emergence of the RSI epidemic, these services became adapted to treat people with problems of work-related pain and strain.

Since the early 1980s, after government intervention, rehabilitation has become a multi-million dollar business. In some cases large business organizations and government authorities set up their own internal organizations, perhaps using some outside services as well, such as specialized ergonomic advice or contract occupational medical facilities.

Some self-styled ergonomics experts appeared, and a large industry developed to manufacture ergonomic furniture, document holders, wrist rests, anti-RSI spectacles, and other devices. Others who prospered included some lawyers and doctors.

In the last year in Australia there has been a severe shake-out among these professionals, with survival of consultants partly dependent on acceptance by unions. However, important and increasingly successful principles of rehabilitation have emerged. These include:

1. information and appropriate training at all levels of management,

2. early reporting of cases, onals, politicians, journalists and many

others in Australia made numerous

3. careful and detailed assessment of affected employees, typically taking

several hours,

4. co-ordination of medical, paramedical, management, social, and other

short-term aches could develop into chronic pain problems without a

resources, if victims were repeatedly told they were injured. These were

probably

5. ergonomic job analysis, by suspect assertions of proof of non-specific

overuse injury, based on

6. modifying work to match the capacity of the rehabilitee, microscope

study of tissues from muscles which have been rested for many

7. monitoring individual progress, and setting realistic goals, typically

with a return to full work over several weeks,

8. monitoring overall Occupational Health and Safety (OH&S) statistics

carefully, and

9. accepting OH&S as a responsibility of line management, and the

relationship between accident rates and good industrial relations and

management techniques.

Managers of large organizations such as factories and offices had been frustrated by their inability to cope with the epidemic of reported cases. Many of these were written off with compensation pay-outs. Some large firms developed rehabilitation services with token jobs. When these failed to achieve return of affected employees to work, more skillful and professional approaches to job modification and graduated programmes of increasing workload were developed.

Follow-up and statistics for success rates of rehabilitation in this series are not available, but there is an impression that current rehabilitation methods have proved successful.

One successful form of intervention has been to employ an occupational

physiotherapist to monitor staff before they made formal complaints of

symptoms, and to detect and correct potential problems, such as bad seating,

job design, work habits or neck posture.

Other factors

The diagnosis of psychogenic pain is notoriously difficult. It is made partly by exclusion, and partly on positive evidence (Engel, 1959). Where organic and psychological causes for symptoms co-exist, the problem is of course much harder. While observations were made in the present series, results have not been analysed for the present study except to note the relation of anger to muscle tension. However, there often appeared a progression from acute physically-based symptoms, anger, or both, to chronic pain without evident physical basis. There were other cases which had no physical basis from the start, as shown by the group of cases with distorted symptoms.

Professionals, politicians, journalists and many others in Australia

made numerous public statements about RSI during the years of this study.

Role models for pain behaviour are well known in other situations, and

unions failed to understand that reversible short-term aches could develop

into chronic pain problems if victims were repeatedly told they were injured.

They were probably fuelled further by suspect assertions of proof of non-specific

overuse injury, based on electron microscope study of tissues from muscles

which had been rested for many weeks (Dennett and Fry, 1988) and mirrored

by publicity for controversial conditions of vague pains

attributed to virus infections such as benign myalgic encephalomyelitis

and `chronic fatigue syndrome'. There was also a delay in appreciating

the role of poor management style in generating these problems. Such factors

are outside the scope of the present discussion.

Neck and arm pain are common symptoms among VDT operators. In this study a combined ergonomic and medical approach suggests that common but preventable causes include bad habits of work, hand position, neck posture and poorly planned rehabilitation. The data in this study provide some support for the role of these factors, but the numbers of cases are small, and more carefully planned prospective studies of these factors are needed quickly.

Basler, A. and Kawaletz, K., 1943, Uber den Einfluss des Konstitutionstypus

auf die Technik des Geigenspiels. Arbeitsphysiologie 12. Quoted in: The

Physiology of Violin Playing, O. Szende and M. Nemessuri, 1971 (London:

Collett's).

Cakir, A., Hart, D.J. and Stewart, T.F.H., 1980, Visual Display Terminals:

A Manual Covering Ergonomics, Workplace Design, Health and Safety, Task

Organization (Chichester: Wiley).

Dennett. X. and Fry. J. H. F.. 1988. Overuse syndrome: a muscle biopsy

study. Lancet, i, 905-908.

Elvey, R. L., 1979, Brachial plexus tension tests for the pathoanatomical

origin of arm pain. In: Aspects of Manipulative Therapy, pp. 105-110 (Melbourne,

Australia: Lincoln Institute of Health Sciences).

Engel, G. L., 1959, 'Psychogenic pain' and the pain-prone patient. American

Journal of Medicine, 86, 899-918.

Ferguson, D. A., 1971, Repetition injuries in process workers. Medical

Journal of Australia, 2, 408-412.

Gowers, W. R., 1888, A Manual of Diseases of the Nervous System, Vol.

II (London: Churchill).

Grandjean, E., Nakaseko, M., Hunting, W. and Gierer, R., 1985, Researches

on ergonomically designed alphanumeric keyboards. Human Factors, 27(2),

175-185.

Greig, J. and Caple, D., 1986, Key activation pressure as a factor in

typing techniques. Proceedings, 23rd Annual Conference, Ergonomics Society

of Australia and New Zealand, pp. 257-265.

Hocking, B., 1989, 'Repetition strain injury' in Telecom Australia. Medical

Journal of Australia, 150, 724.

Hult, L., 1954, The Munkfors investigation. Acta Orthopedica Scandinavica,

Supp1.16: 1-76. Quoted in Medical Management of the Regional Musculoskeletal

Diseases N. M. Hadler, 1984, (Grune and Stratton).

ISO, 1971, Alphanumeric keyboard operated with both hands. ISO 2126 (Geneva:

ISO).

Malt, L. G., 1977, Keyboard design in the electronic era. Paper presented

at the Printing Industry Research Association Eurotype Forum, London,

September. Conference Paper No. 6.

Mathews, J., 1985, Health and Safety at Work. Australian Trade Union Safety

Representatives' Handbook (Sydney: Pluto).

McKenzie, Robin, 1983, Treat Your Own Neck (Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal

Publications).

NHMRC, 1982, National Health and Medical Research Council. Approved Health

Guide: repetition strain injuries. Canberra, AGPS, 1982: 1.

Patkin, M., 1984, Trying too hard. In: Proceedings, 21st Annual Conference,

Ergonomics Society of Australia and New Zealand, pp. 298-301.

Patkin, M., 1987, Occupational strains in school children - do they exist?

Australian Educational Computing, 2(1), 14-22.

Patkin, M., 1988a, Excess effort and pain at work. The missing ergonomic

factor. Designing a Better World, Proceedings, 10th Congress, International

Ergonomics Association, Ergonomics Society of Australia, 1, 248-250.

Patkin, M., 1988b, Hand and arm pain in office workers. Modern Medicine

ofAustralia, 31(10), 66-76.

Rose, M., 1986, Development of ergonomic keyboards. Proceedings, Australian

Institute of Industrial Engineering, Conference, Sydney, 1986, pp. 17.1-17.16.

Seymour, W.G., 1966, Industrial Skills (London: Pitman).

Spillane, R. and Deves, L., 1987, RSI: pain, pretence, or patienthood.

Journal of Industrial Relations, 29, 41-48.

Stack, B., 1988a, Repetitive strain injury - prevention and rehabilitation.

Proceedings, First International Congress on Ergonomics, Occupational

Health and Safety and the Environment. Beijing, in press.

Stack, B., 1988b, New design concepts in wrist rests, desks and keyboard

supports. Preprints of International Conference on Ergonomics, Occupational

Safety and Health and the Environment, 1, 444-453.

Taylor, R., Gow, C. and Corbett, C., 1981, Process Workers' Arm. Workers

Health Centre, Lidcombe, New South Wales, Australia.

Welch, R., 1973, Ergonometrics of tenosynovitis. In: Occupational Injuries.

Seminar Manual, pp. 145-147. Royal Australian College of Surgery.

Wright, G.D., 1987, The failure of the 'RSI' concept. Medical Journal

of Australia, 147,233-236.

-o0o-

Contents

Introduction

The common overlooked causes

Muscle tension

Hand position

Neck posture

Sudden high work load

Materials and methods

Early observations

The present series

Observations

Occupational groupings

Muscle tension

General habitus

Handwriting faults

Other movements at work

Results of treating excess tension

Office workers

Typing

Writing

Non-office workers

Cleaning

Hammering

Morse-key operators

Musicians

Hand position

Neck posture

Findings using the BPTT

Rehabilitation

Discussion

The Australian experience

Muscle tension

Timing

Further aspects - EMG,

equipment, maintenance, anger

Hand position

Neck posture

Rehabilitation

Other factors

Psychogenic pain

Dogma and social attitudes

Neck and Arm Pain in Office Workers:

Causes and Management

_________________________

(from Michael Patkin, Chapter 13, Neck and arm pain in office workers: causes

and management, in Promoting health and productivity in the computerized

office: Models of successful ergonomic interventions. Ed. S. Sauter , M.Dainoff,

& M.J.Smith, p. 207-231. Taylor & Francis 1990)

_________________________