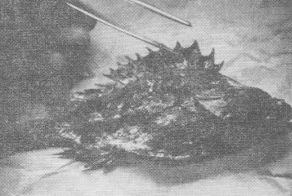

A condition that is rare, spectacularly painful, badly documented, and easy to treat appears worthy of record. If the pathological features are bizarre, the record gains added point. Such considerations are shown by the sting of the bullrout (Notesthes robusta), a fish found in the rivers of northern New South Wales (Figure 1).

.

The bullrout is a member of the scorpion-fish family prevalent in, south-eastern Australia, and it is related to the red rock cod (Ruboralgia jacksoniensis). It is several inches long, has a bony ridge from above the eye to the preoperculum bearing 15 spines, and resembles the rocks and weeds among which it may be found. It is usually met with in muddy river shallows, and is rarely, if ever, seen by the unfortunate victim of its sting (C.S.I.R.O., 1943.)

The history is most characteristic. A young person wading in a river during summer feels a sudden sting in the foot, followed within seconds by severe pain, which becomes excruciating. A little slit about 2 mm long is seen on the plantar surface of the foot, often on its outer edge, or on a toe. Sometimes this is duplicated half an inch away, or, rarely, more puncture marks are present (Figure 2).

There is a little oedema, insufficient to pit, some pallor or erythema for about 2 cm about it, and surprisingly little tenderness. There may be localized sweating.

A curious feature is a lesser degree of pain complained of in the main regional lymph nodes; no swelling or tenderness of these has been found, but the site is not open to doubt after examination.

The patient is badly distressed, restless and often tearful, but not shocked. The temperature remains normal. The clinical picture is so typical that the diagnosis has never been in doubt. It is usually made by local inhabitants or by the nursing sisters or nursing aides on duty at the hospital.

Sixteen patients with bullrout sting were treated at the casualty department of the Dungog and District Hospital in the five years from February, 1963, and there have been a few further cases treated at the surgery, of which records were not readily available. During this time, 1,452 out-patients were examined at the hospital, giving an incidence for this emergency of l%. This is an underestimate, in view of a proportion of elective minor surgical procedures.

Over the same period of time, various stings and bites have occurred, as follows: bee-stings, three cases; wasp stings, one; spider-bite, four (of which two from redback spiders required prolonged hospital admission) ; snakebite, two (both patients were admitted to hospital; ticks, two, and a platypus sting.

Of the 16 cases of bullrout sting, eight were in visitors to the area; the other eight patients lived locally. This is noteworthy as, apart from accident victims and medical emergencies, few visitors are seen in. the practice. The age incidence, when recorded, varied from 8 to 22 years, with an average of 15 years. Only four patients were girls, representing 25% of the total. The seasonal incidence was striking. All except one case occurred between November and February.

The bullrout is most likely to sting a person wading in a river with muddy floor, near reeds. Bullrout stings seem to have become much less common in the Paterson River at the nearby town of Gresford over the past 10 years, possibly owing to the influx of large quantities of sand from further up the river. All cases treated in Dungog have occurred in the Williams River, a tributary of the Hunter, either at Dungog, or at Clarencetown, both popular places for swimming during the summer.

Current treatment of bullrout stings can hardly be simpler. The area is infiltrated through the puncture wound itself with 2 to 5 ml of 101o or 2% lignocaine. This is followed by relief of pain within seconds. Relief is complete within 15 to 30 minutes, and a statement frequently volunteered is that the pain has left the groin. In. one case out of the 16, the pain recurred with its excruciating initial severity after half an hour, when the patient was already on his way from the hospital. A second injection appeared effective, although in this case pethidine also was given intravenously. This technique appears to have been described first by Hewitt (1943), who at that time used "Novocain".

In no other cases in this series have other analgesics been given, nor has there been any need for their use. One patient not included in this series had been treated for a bullrout sting by injection of morphine, apparently by a doctor unfamiliar with the condition. This patient stated there had been no noticeable relief of his pain for some hours. A doctor who was previously in Dungog and who was known to one of us had also stated that he had no relief of pain from an injection of morphine for a bullrout sting.

Treatment with local anaesthesia has usually been given to patients 10

to 30 minutes after they have sustained a sting. This represents the time

for the patient to be brought to hospital and for the doctor to be summoned.

The necessary injection is drawn up and ready for use by the time the

doctor arrives.

Duration of pain in the absence of treatment is uncertain, but probably

a matter of hours to a day. A local tradition, difficult to test and probably

wrong, states that the pain lasts till sundown.

Antibiotics have not been given, but antitetanus treatment has been administered without enthusiasm as a routine. No complications have been noted in patients living in the area of the practice and available to follow-up.

Earlier methods of treatment in the Dungog area have comprised infiltration of the wound with emetine, which has been stated to be effective by doctors and nurses in the area previously. Two patients with bullrout stings at Gresford, about 30 miles away, were treated by the doctor there with local injection of potassium permanganate. After 20 minutes, they were able to walk out of the surgery in comfort (Short, quoted by Wiener, 1958). Among local residents, a method of treatment mentioned is the application to the site of the sting of tar from a tobacco pipe.

There are few accounts of bullrout sting, and all except one that were traced were over 50 years old. Cleland, writing in 1912 on injuries from Australian animals, merely quoted an earlier author's work on the Great Barrier Reef for his description of the sting of the bullrout.

… the pain is intense. It runs through the whole limb like fire. The injured part becomes red and inflamed. But except the pain, which all victims assert is very agonizing, there. are no serious consequences . . Its sting is most frequently felt by bathers, who tread upon it as it lies on the bottom among the weeds. The blacks hold it in great dread, and the name of Bull-rout may possibly be a corruption of some native word. The venom is probably a mucus secreted by the skin, and not connected with any distinct poison gland.

Kesteven (1915) described symptoms at variance with present experience, and also exaggerated the dangers. He noted:

… the rapid appearance of an erythematous blush, which spreads around the wound for some distance, in a manner not noticeable in ordinary incised wounds; the pain is out of all proportion to the very insignificant nature of the injury; it radiates in an altogether abnormal manner, compared with ordinary pricks or scratches, in many cases extending to the shoulder, or even up the side of the neck; the temperature varies greatly, in most cases going up two, three, or more degrees within a very short time; lasting thus for a varying time, and going down again as rapidly, often below the normal, when severe collapse occurs, necessitating the free administration of stimulants to counteract the heart failure which threatens.

Cases treated as in the ordinary methods for snakebite-chiefly I have found permanganate the most efficacious-can be relieved considerably if taken in hand soon after the sting; but. if the poison has had time to put in its fine work, so much longer does the recovery take. Extreme prostration, for several days, often follows the stings, leaving the patient weak and exhausted.

The symptoms are not compatible with non-toxic wounds. They are undoubtedly venomous.

A further paper by Cleland (1915) quotes Kesteven's description verbatim, and reports a further case, at secondhand, from the Tweed River.

Great pain was at once felt; strong ammonia was applied; the agony was excruciating for some hours, accompanied with much perspiration; the patient could not sleep. Next day the foot was much swollen, and remained so for several days, a red spot indicating the part bitten. The patient was naturally not able to get his boot on.

Pacy (1962) provides a good description of the comparable injuries of the stings from catfish and stingrays, met with on the coast. Excruciating pain, which may last for days, swelling of lymph nodes, sometimes multiple, are accompanied by intermittent watery discharge from the wound. The venom in these cases has been shown to be a vasoconstrictor, and there may be actual numbness about the puncture mark. His treatment in these cases is local infiltration with 3 ml of a "Xylocaine"hyaluronidase mixture, but he also recommends a tourniquet and potassium permanganate irrigation of the wound as first-aid measures. He also mentions the local injection of emetine.

In a comprehensive review of dangerous Australian fishes, Whitley (1963) quotes a newspaper report of a bullrout sting in which the victim described severe swelling at the site and agony for 11 days.

The description nearest our own experience is that of Hewitt (1943), who found the feet the usual site for injury, especially the great toe.

The punctures are usually single, but may occasionally be multiple. There is no doubt as to the intensity of the pain, coming on immediately it radiates along the limb to the groin (in the case of a foot), children often become almost maniacal and adults writhe in agony, collapse is sometimes severe. For many years we have injected hypodermically a solution of "Novocain" ("Adrecain") 1% in amounts of one to three cubic centimetres, if possible along the punctured wound. The effects have been immediate and dramatic, both local and radiating pain disappearing rapidly.

Several points of academic interest emerge in relation to bullrout stings. The relief of severe pain in these cases is much quicker than the development of anaesthesia around a laceration about to be sutured. Wiener suggests this may be a pH effect. The local anaesthetic used in this series has a pH of 6-1, suggesting that the venom may be alkaline. This may explain the misery of the patient of Cleland's mentioned above, who had ammonia applied to his wound. The rapid development of pain in the regional lymph nodes, and its equally rapid cure, may be of interest to those who study the mysteries of immunology.

Is there more than one type of bullrout sting? A search of the Dungog register of deaths from 1862 onwards has disclosed no death ascribed, even in part, to a bullrout sting, despite many other curious types of trauma recorded. Kesteven may have drawn his conclusions from more northerly areas, where the sting may be more severe. In Queensland, stingings from the bullrout have produced symptoms as severe as those caused by the stonefish of evil repute (J. Trinca, 1968, personal communication). This could justify manufacture of an antivenene, whereas the experience reported in this series certainly would not.

As is natural, only severe reactions to such events as a bullrout sting are remembered or recorded. The case of Cleland's, already referred to, quite likely was complicated by a bacterial cellulitis. By contrast, stinging injuries sustained by fishermen netting prawns in the Hunter River at Maitland, from a small fish known as a fortesque, do not lead the victim to seek medical advice.

The ineffectiveness of morphine in two cases mentioned earlier, neither of which belonged to the series available for study, is not to be taken as conclusive. The dose given in each case is not known, and it is possible that larger doses than normal may have effected relief. On the evidence presented, however, it cannot be advised as the initial treatment. Infiltration with a local anaesthetic is the method of choice for relieving patients of their pain, being simple, effective, and mercifully quick.

In the preparation of this paper, much help was provided by Miss A. Harrison, Medical Librarian at the University of Melbourne, Miss M. Rolleston, Librarian to the New South Wales Branch of the Australian Medical Association, Dr Saul Wiener of Melbourne, Dr John Trinca of the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, Dr George Hewitt of Bellingen, Mr Athol D'Ombrain of Maitland, Mr Gilbert Whitley of the Australian Museum, Sydney.

The bullrout illustrated in Figure 1 was presented to the Dungog Historical Museum by Miss Margaret Dowling, of Caningalla, Dungog. Local knowledge was gained with the help of the late Charles Bennett, M.B.E., Editor of the Dungog Chronicle.

Since this paper was submitted, the writers have had opportunities of examining the bullrout fish at first hand, and the following points of interest were noted. On dissection of the bullrout, an air sac with a capacity of several cubic centimetres was found dorsal to the stomach. This adds credence to accounts of a noise made when the fish is moved out of water. A live bullrout, presented by Mr Russell Morris and Mr M. S. Berry of Dungog, was observed in a large plastic dish of water. The bullrout lay, hardly moving, at rest on the. bottom, and with its spines flattened on the back. When provoked with a piece of stick, the fish would suddenly erect the whole row of dorsal spines and make vigorous and agitated movements. This would seem the likely method of injury in those unlucky enough to be stung.

CLELAND, J. B. (1912), "Injuries and Diseases of Man in Australia

Attributable to Animals (Except Insects)", Aust. med. Gaz., 2: 269.

CLELAND, J. B. (1916), "Injuries and Diseases of Man in Australia

Attributable to Animals", Report to the Director General of Public

Health, New South Wales: 266.

C.S.I.R.O. (1943), "Poisonous and Harmful Fishes", Bulletin

No. 159: 21.

HEWITT, G. (1943), "The Treatment of Bullrout Lesions", MED.

J. AUST., 2: 491.

KESTEVEN, L. (1915), in Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South

Wales, 1914, Part 1: 91.

PACY, H. (1962), "Stingray and Catfish Injuries in New South Wales",

MED. J. AUST., 1: 119.

WIENER, S. (1958), "Stone-Fish Sting and Its Treatment". MED.

J. AUST., 2: 218.

WHITLEY, G. P. (1963), "Dangerous Australian Fishes". Bull.

post-grad. Comm. Med. Univ. Sydney, Suppl. 12: 59.

AUSTRALASIAN MEDICAL PUBLISHING COMPANY LIMITED 71-79 Arundel Street,

Glebe, Sydney, N.S.W., 2037

-o0o-

Contents

Clinical features

Incidence

Treatment

Discussion

Acknowledgements

Addendum

References

Reprinted from The Medical Journal of Australia, 1969, 2: 14 (July 5)

Bullrout stings

MICHAEL PATKIN, M.B., B.S. (MELB), F.R.C.S., F.R.C.S. (EDIN.), F.R.A.C.S.,

AND DAVID FREEMAN, M.A. (CANTAB.), M.B., B.CHIR.(CANTAB.), M.R.C.S., L.R.C.P.(LOND.)1

Dungog, New South Wales

'Present address: Hammersmith Hospital, London.